The China puzzle

In 2020, China was the standout equity market, yet chances are if you were invested in Chinese shares via exchanges not on the Chinese mainland your returns may not have matched the local bourses’ return. Technology stocks have been subject to regulatory demands and high profile episodes such as the non-listing of Ant Financial has weighed on investors’ sentiment.

Into 2021, there has been a popular narrative that there is a large, coordinated regulatory push in China. That narrative is easy to sell in today’s 24-hour news cycle, but there is more to China’s apparent regulatory extension. An understanding of underlying mechanisms can help foreign investors navigate their exposure to what is becoming the world’s largest economy.

The actions of authorities in China dominate headlines. However, if the name of the country is not mentioned, many of the moves are sensible:

- Tightening up on the (mis)use of personal and potentially sensitive data

- Providing decent, affordable, quality education

- Providing occupational insurance for “gig” workers

- Preventing monopolistic behavior and enhancing competition

- Opening up the financial system to wider foreign participation.

You might remember when then-US president Barack Obama took on the American for-profit college sector, passing the “gainful employment” rule that took away eligibility for government education loans from schools whose graduates did not land well-paying jobs. This decimated the sector. While the intention of that rule was to target fraudulent for-profit colleges, the point is developed governments can, and occasionally do, all but end industries.

Just last month, again in the US, a House of Representative committee approved far-reaching legislation to curb the market dominance of tech giants. The legislation aims to restrict big tech companies’ ability to leverage their platform dominance to promote other lines of business and disadvantage competitors. Big tech companies face being barred from favouring their own products and would be required to make it easier to transport data between users. The Wall Street Journal reported, “lobbyists and trade groups for the large tech companies were complaining that the House bills are being rushed through with little thought to the impact they will have on consumers.” No doubt, if this was China the prices of Google, Apple, Amazon and Facebook would tumble. There will however be opportunities to block or water down the legislation before it becomes law.

The dominance of big-tech and monopolies concern US legislators, as they do legislators around the world, like China. The difference is the approach. There are no committee hearings, or cross-party negotiations. This past week has highlighted that.

The Chinese government has made no secret its mission is to promote “common prosperity”, these being the policy keywords. This entails action in four areas: property, education, healthcare and livelihood.

Property – Authorities are aiming to stabilise property prices. Property developers are highly leveraged, and the government has drawn some lines in the sand to keep those levels under control. There is also a decent-length grace period for this to happen. At the company level, Evergrande, has liquidity issues and despite reporting is not the sector. We expect to see some more measures, such as implementing a property tax and possibly mandating a percentage of affordable housing. Longer term, this will mean developers have lower, but less cyclical margins.

Education – While the severity of the new measures for tutoring is surprising, the fact that regulations were coming was not. In March, President Xi Jinping called after-school tutoring services a “social problem,” and in May, he again lashed out at the industry’s “disorderly development.” One of the major purposes of the new rules is to “effectively ease the anxieties of parents,” as well as reduce family spending on education. A major obstacle for Chinese citizens to have more than one child is the cost of doing so, and quality education was a part of that cost. These measures also have the long-term goal of increasing the birth rate.

Healthcare – The government knows healthcare spending will increase as the population ages, and the key issue is to provide the triumvirate of quality, access and affordability. The government will continue to reduce the prices for medicine, equipment and in the future, services, while encouraging innovation.

Livelihood – So far this has taken the form of breaking up monopolistic behavior. A good example was the fallout from Ant Financial. Chinese authorities were concerned Ant Financial’s business model, which was in part sourcing loans and passing their risk onto commercial banks, did not promote a level playing field. The government has also taken aim at its potentially monopolistic practices in its core e-commerce business. The creation of China’s wealth in the internet industry has been fast and the government has been concerned the benefit to society and customers has not been as great as it has been for companies. Reining in the power of its monopolistic tech titans limits their influence while boosting China’s start-ups.

What is evident is that these announcements and regulations are industry and/or company specific. These changes affect local investors. Despite some rhetoric, these are not about geopolitical tensions, nor are they targeted at foreign ownership.

So what is an investor to do?

There is no doubt investors need an allocation to what will become the biggest economy in the world, however, there are idiosyncrasies investors need to appreciate, as there always has been.

Investors have always appreciated regulatory risk in Chinese equities. Emerging markets equities, including China A shares, have historically traded at a discount to developed markets. Last week’s price action suggests that it was not fully priced in, particularly in Chinese companies listed in New York or Hong Kong. The impact on the mainland Shenzhen and Shanghai exchanges, while still significant were not as extreme.

China worked hard to have A-Shares included in MSCI and FTSE indices so is not antagonistic toward foreign money. It wants to strengthen its domestic economy and encourage capital to go to industries it wants to develop and stay away from areas it deems a threat to the common good. These will be A-Shares.

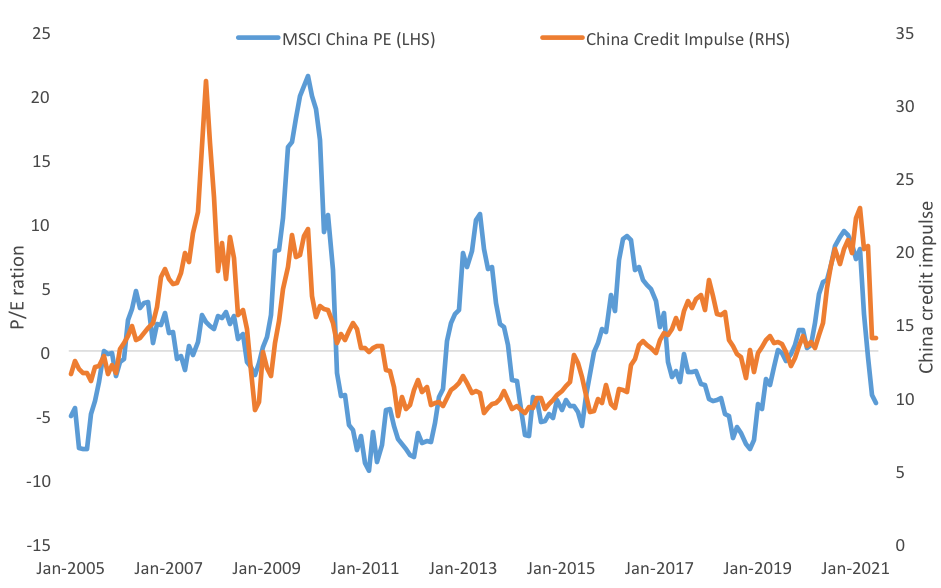

MSCI China A shares price to earnings (P/E) valuation multiple tends to be pro-cyclical or expand and contract with the credit impulse in China (chart 1). The slowdown in the rate of change in credit is well advanced and might start to improve again later this year. There may be tremendous opportunities being thrown up here, by blind indiscriminate selling. It could be that in the second half of 2021 A-shares will emerge after panic sentiment fades away among onshore and offshore investors.

Chart 1: China valuations and China credit impulse

Source: Bloomberg, 30 June 2021

Published: 29 July 2021

VanEck Investments Limited ACN 146 596 116 AFSL 416755 (‘VanEck’) is the responsible entity and issuer of units in the VanEck China New Economy ETF (CNEW) and the VanEck FTSE China A50 ETF (CETF). This is general advice only, not personal financial advice. It does not take into account any person’s individual objectives, financial situation or needs. Read the PDS and speak with a financial adviser to determine if the fund is appropriate for your circumstances. The PDS is available here.

An investment in CNEW or CETF carries risks associated with: China; financial markets generally, individual company management, industry sectors, ASX trading time differences, foreign currency, sector concentration, political, regulatory and tax risks, fund operations, liquidity and tracking an index. See the PDS for details. No member of the VanEck group of companies guarantees the repayment of capital, the payment of income, performance, or any particular rate of return from any fund.