What the Australian fund management industry learned from taxis

At the time, the share ride service, Uber, was often referred to as a disruptor to taxis. Uber provided a similar, more convenient service, but at a lower cost.

Lower costs themselves are not an innovation, they might be the result of innovation. While low costs can disrupt an industry in a literal sense, a low-cost product is not always a ‘disruptive innovation’.

Unlike the taxi industry, some players in the Australian fund management industry have been looking at innovations and positioning accordingly. One of these has been identified as ‘disruptive.’ To find true disruptive innovation, investors also need to consider more than lower costs.

In The Innovator's Dilemma, Harvard Business School’s Professor Clayton Christensen introduced the concept of disruptive innovation. “Products based on disruptive technologies are typically cheaper, simpler, smaller and frequently more convenient to use.”

In the age of new technologies and AI, the term disruption is being used more frequently. But we think it’s worthwhile for investors to understand the difference between disruption and disruptive innovation.

During the early, heady days of Uber’s phenomenal customer growth rate, an article in Harvard Business Review co-authored by Clayton Christensen suggested the term disruption is now used too loosely and is used “to describe any situation in which an industry is shaken up and previously successful incumbents stumble.”

Using the framework Christensen developed in The Innovators Dilemma, Christensen and his co-authors debunked the claim that Uber was a disruptive innovation.

Applying his own framework from his book Christensen pointed out, Uber did not originate in a low-end market or in a new market foothold. This is necessary to classify it as a disruptive innovation. Uber, Christensen and his co-authors argue, improved on, and developed a better solution to a widespread need. Uber started in the mainstream market competing head-on for customers who were already in the habit of hiring taxis. Further Uber is not a low-end opportunity, “that would have meant taxi service providers had overshot the needs of a material number of customers by making cabs too plentiful, too easy to use, and too clean. ” (Christensen et al).

Uber instead is a ‘sustaining innovation,’ which means it makes an existing product or service better. Sustaining innovations were also defined by Christensen in The Innovators Dilemma. Uber is cashless and convenient.

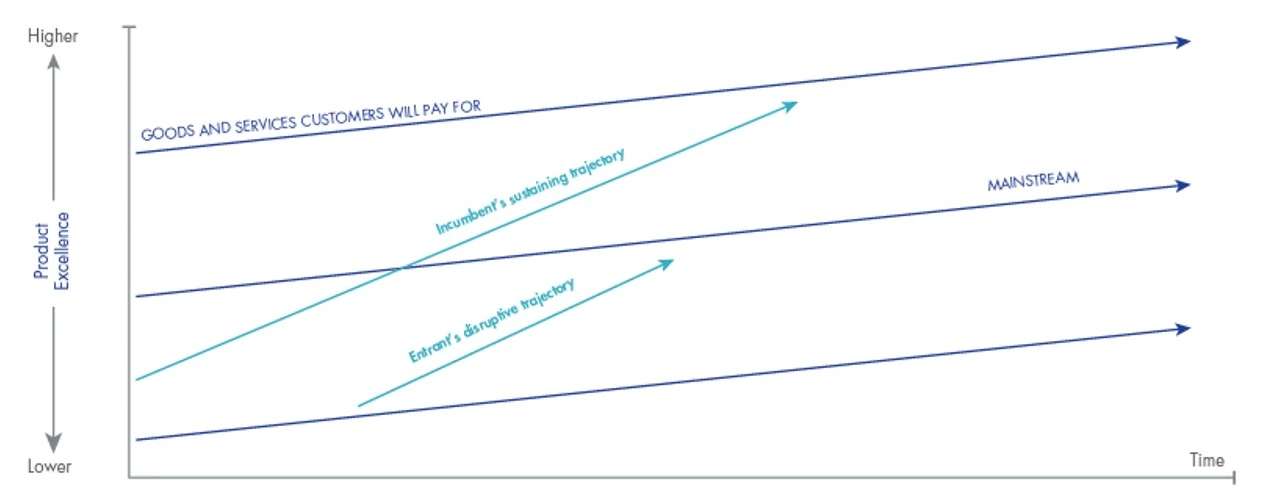

“Disruptive innovations, on the other hand, are initially considered inferior by most of an incumbent’s customers. Typically, customers are not willing to switch to a new offering merely because it is less expensive. Instead, they wait until its quality rises enough to satisfy them.” (Christensen et al).

Chart 1 – The disruptive innovation model

Source: Christensen et al 2015, "What is Disruptive Innovation", Harvard Business Review, December.

The Australian fund management industry arguably has similar traits to the taxi industry 10 years ago, high fees and poor service were prevalent. The Australian fund management industry is supported by a savings system all Australian employees are a part of, that is superannuation. Many funds are able to rely on new investment flows from the compulsory scheme, irrespective of performance.

Somewhere along the way, Australian investors got wise to active management underperformance, and low-cost passive funds that tracked traditional market capitalisation-weighted benchmark indices became prevalent.

In the earlier part of the century, investors were able to start buying these passive funds on the ASX via exchange traded funds (ETFs).

ETFs, at the time, were an exciting innovation offering investors low-cost passive funds that tracked an index. The first ETF on ASX tracked the performance of the Australian market capitalisation index, the S&P/ASX 200.

ETFs, like Uber, were a sustaining innovation. They are more convenient, more transparent and more liquid. And they led to lower costs.

The mechanism of (lots of) trading on the exchange had the impact of making buy/sell spreads cheaper for clients. ETFs were the mechanism that allowed for lower fees.

Liquidity was the innovation, not the fees. Transparency was the innovation, not the fees. Convenience by the ease of trading (and no application/redemption forms) was the innovation.

The adoption of ETFs, like the adoption of ride-sharing services, has been swift. There is now around $150 billion invested in ETFs on ASX.

Other ‘sustaining’ improvements for investors on ASX have been the introduction of active ETFs and, more recently, even lower costs.

Lower costs associated with improvements in processes are an innovation. Lowering costs for the purpose of gaining a competitive advantage is not innovation and may point to a manager that has run out of ideas to help its clients navigate the gauntlet of investment markets.

While low costs are often seen as a win for investors, investment outcomes are not the fees paid. Investment outcomes are important and while it is natural investors want to pay less, they also want to achieve their objectives, be it growth, diversification or stable, consistent income.

There are disruptive innovations on ASX, which satisfy Christensen’s criteria. You just need to know where to look.

Disruptive innovation on ASX

We think smart beta is a disruptive innovation that has the potential to change the landscape of the Australian fund management industry.

We are not the only ones.

The CFA Institute’s own Financial Analysts Journal published an article by Ronald Kahn and Michael Lemmon titled “The Asset Manager’s Dilemma: How Smart Beta is Disrupting the Investment Management Industry.”

Smart beta is an index strategy that involves a methodology for construction that differs from traditional market capitalisation-weighted benchmark indices. Examples of smart beta include equal weighting and filtering stocks using identifiable filters such as quality or value.

Smart beta indices are created using rules-based selection criteria with the intention of targeting investment outcomes. Some ETFs track these smart beta indices.

Smart beta ETFs are attractive compared to active funds due to:

- lower costs;

- explicit rules-based methodology;

- transparency; and

- reduction of risks, including key man risk.

In sync with Christensen’s framework, smart beta originated in the low-end market. Institutional investors have used them as a low-cost way to invest and their genesis can be traced back to the 1970s.

Often smart beta has been a part of an active management incumbents’ process as they have been trying to provide their most profitable and demanding customers with ever-improving products and services. These demanding requests, while being met, have created a market for investors’ needs (as opposed to wants). “In the case of smart beta, the investment outcome is higher returns and/or lower risk after fees and costs. The innovation is motivated by the vision of how clients ought to invest – even when they do not realise a change is needed.” (Kahn and Lemmon).

Kahn and Lemmon determine smart beta is:

“a disruptive financial innovation with the potential to significantly affect the business of traditional active management. They provide an important component of active management via simple, transparent, rules-based portfolios delivered at lower fees.” (Kahn and Lemmon, 2016)

The disruption takes time.

According to Christensen, disruptive innovations don’t catch on with mainstream customers until quality catches up to their standards.

In the case of smart beta, quality in the eyes of the investor is its track record. Incumbents and their customers are wary of back-testing. However, once the track record catches up to the customer’s standards, they will adopt the innovation if they can see its benefits.

And Australian investors are starting to see the benefits. Both VanEck’s Australian Equal Weight ETF (MVW) and its International Quality ETF (QUAL) are smart beta ETFs that have been listed since 2014 and have strong performance track records. As does VanEck’s smart beta offerings in A-REITs (MVA), emerging markets (EMKT), US equities (MOAT) and international small companies (QSML).

Published: 14 July 2023

References

Christensen, Clayton M, 1997. The Innovator’s Dilemma. New York: Harvard Business School Press.

Christensen, Clayton M, Raynor, Michael E., and Rory McDonald 2015. “What Is Disruptive Innovation.” Harvard Business Review (December).

Kahn, Ronald N., and Michael Lemmon, 2016. “The Asset Manager’s Dilemma: How Smart Beta Is Disrupting the Investment Management Industry.” Financial Analysts Journal Vol. 72, no. 1.

Any views expressed are opinions of the author at the time of writing and is not a recommendation to act.

VanEck Investments Limited (ACN 146 596 116 AFSL 416755) (VanEck) is the issuer and responsible entity of all VanEck exchange traded funds (Funds) listed on the ASX. This is general advice only and does not take into account any person’s financial objectives, situation or needs. The product disclosure statement (PDS) and the target market determination (TMD) for all Funds are available at vaneck.com.au. You should consider whether or not an investment in any Fund is appropriate for you. Investments in a Fund involve risks associated with financial markets. These risks vary depending on a Fund’s investment objective. Refer to the applicable PDS and TMD for more details on risks. Investment returns and capital are not guaranteed.