IMF Fall takeaways: Emerging markets in the shadow of the US election

Key takeaways

- Investors were preoccupied with the pending outcome of the US Presidential election during IMF sessions, with the majority correctly expecting a Trump win but not GOP control of Congress. Price action and investor sentiment indicate the “Trump trade” of long US dollar and short US Treasuries is largely hedged in emerging market risk assets.

- President-elect Trump’s stated policy on restricting immigration to the US, reducing the immigrant labour force, placing large tariffs on important trading partners, and cutting taxes are all inflationary and risk raising R* in the US along with long-term inflation expectations and rates.

- There was a consensus that tariff policy would not be as damaging as feared, with Trump using the threat of large tariffs, including against China, as a negotiating tool to quickly reach trade-positive agreements for the US. Asia-based investors stated a preference for this electoral outcome.

- Oil prices were expected to decline on large increases in non-OPEC+ production in 2025 and the Trump administrations focus on increasing US production. EM oil importers such as Turkey, CEE, South Africa and Asia stand to benefit.

- Investors continue to downplay the impact of the Chinese stimulus measures being unveiled by Beijing. Many emerging markets economies are set to benefit substantially from increased Chinese growth prospects and a stable Chinese property market.

- Assuming Trump’s most extreme policy proposals do not get enacted, emerging market currencies should benefit from a global growth environment where the world’s two largest economies are stimulating and emerging market governments already know how to do business with the incoming Trump administration. Stability in CNY is a necessary condition for continued EM FX strength.

Investors were anxiously waiting for an outcome

There was a noticeable lack of conviction among EM investors at the fall meetings. The US election was seen as binary and as leading EM assets on two opposing paths. Policymakers often wanted to hear our views on the US election (as if we had some uniquely helpful insight as Americans!). For their part, policymakers could only respond that they would work with whichever party wins and centred discussion on their own economies. Still, the US election used up most of the oxygen in the room and stifled conversations on global macro.

Given the IMF forecasts show barely any change from April, not much was lost. There was a lot of complacency in the consensus views. Only 2% of investors expected global growth to accelerate with almost 80% expecting a continuation of the current moderate growth path. Similarly, the majority expected US core PCE to end next year below 2.5% and just 5% expected it to be above 3%. Regarding US fiscal policy, just 6% of investors expected a reduction in the US deficit over the next 12 months. When asked about the path of the US dollar under a Trump win, just 23% of investors expected a weaker US dollar. And perhaps most importantly, only 25% of investors were planning to increase investments in Chinese assets with 39% still viewing China as not investable. While this is a huge improvement from the just 4% of investors looking to increase investments in China a year ago, there is still a substantial reallocation towards China to come if China follows through with its policy stimulus. In the face of continuous negative sentiment, Chinese assets can climb a wall of worry as economic data improves and policy support continues to increase incrementally over time.

There was also a stated preference from Asian investors for a Trump presidency because they felt Asian governments, including China, could strike a deal with his administration quickly and get back to doing business whereas Harris’ anti-China stance was viewed as ideological and so it would be near-impossible to improve the business relationship with the US under her administration. The conventional wisdom was that President Trump would start with a low tariff rate such as 10% on Chinese goods and increase the rate on a preset schedule in order to pressure China toward reaching a favourable deal. China in return would like to increase foreign investment in its economy.

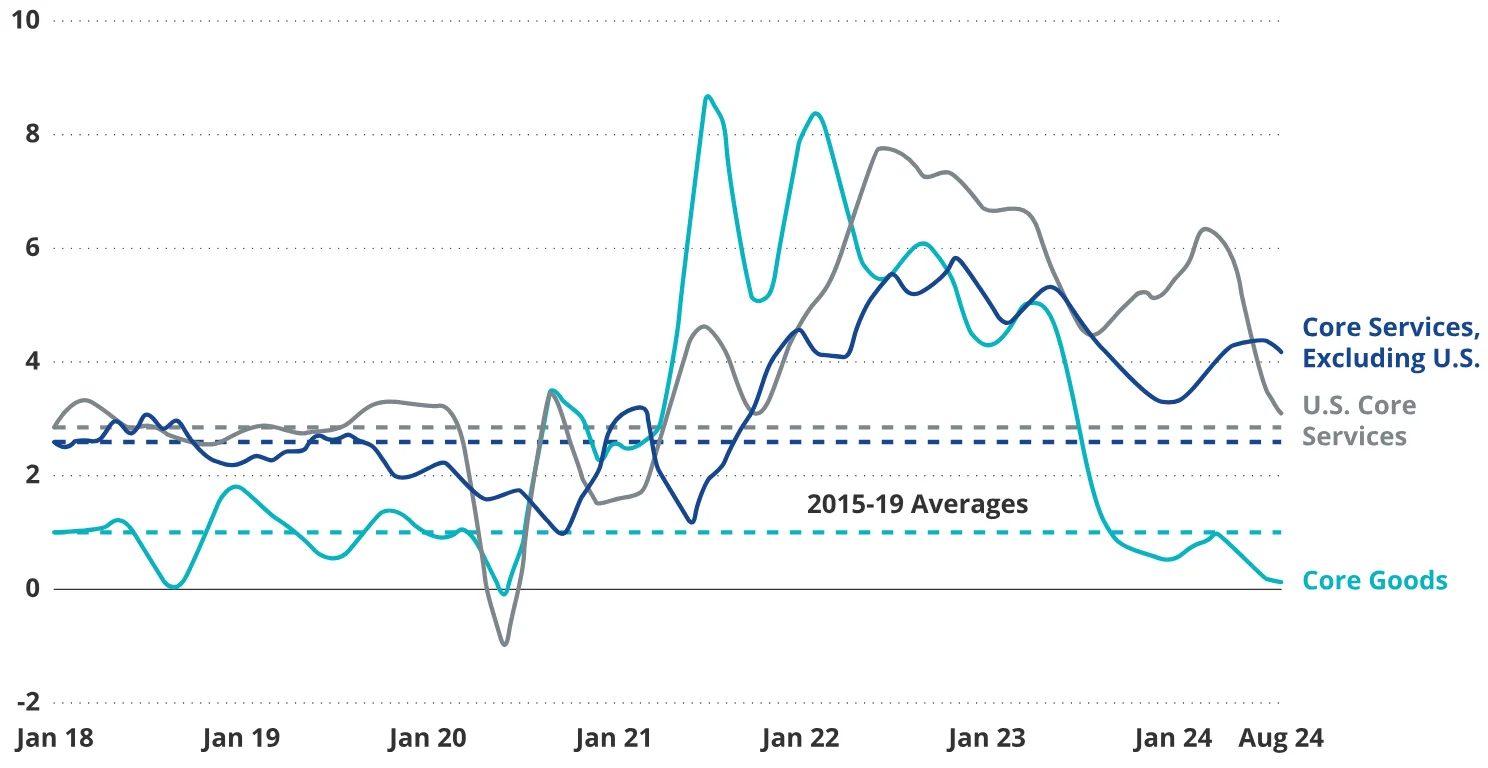

Risks to US monetary policy from services inflation, tariffs, and immigration

The IMF has been warning about sticky core services inflation globally leading to more persistent core inflation. In most advanced and developing economies, while core goods inflation is at or even below target, core services inflation remains 50% above pre-pandemic levels. The continued strength of the US economy along with a healthy labour market and continued pent up demand for services is keeping services inflation high. Additional tax cuts from the Trump administration would only add to that pressure. In contrast, goods inflation has declined to zero thanks to the easing of pandemic related trade bottlenecks and cheap Chinese exports.

Inflation is sticky – driven by services

Chart 1: Percent, three month over three month, annualised

Source: International Monetary Fund, as of October 2024.

There are two potential shocks that may arise from the incoming Trump administration’s policy in January 2025: (1) tariffs, particularly very high tariffs on Chinese goods, and (2) restrictions on immigration to the US and a reduction of the US immigrant labour force. Both shocks could have large impacts on core inflation with tariffs at least temporarily derailing benign core goods inflation.

Under a tariff scenario where Trump implemented his most extreme tariff proposals of an across the board 10% tariff (Mexico and Canada would be exempt under USMCA) and a 60% tariff on China, it would add at least 0.8% to 2025 inflation and 0.6% to 2026 inflation with the impact felt as early as 2Q25. The real impact could be much higher with estimates of up to a 2.5% increase in CPI. There is hope that Trump will start with a more modest tariff rate and use the threat of much higher tariffs to reach a beneficial agreement with trading partners, most importantly China, but the risk is real and material including that no agreement is easily reached, and retaliatory measures are taken.

The second shock coming from restricting immigration to the US and potentially reducing the country’s immigrant labour force would have a longer lasting impact, the damage from which would be much harder to recover. The increase in the US labour force coming from the surge in net immigration during 2022 and 2023 of an average of 3 million per year (vs. an overage of 1mm in earlier years), may have reduced inflation by up to 0.5%. Undoing just this recent positive benefit risks raising 2025 inflation by another 0.5%. However, unlike tariffs, a permanent reduction in the labour force and a significantly reduced rate of new immigrant labour could raise R* substantially by permanently increasing inflation expectations, reducing potential growth and driving both wages and the unemployment rate higher.

The combined shock of higher tariffs and reduced immigration could raise US inflation by at least 1.3% in 2025 which would not only stop the Fed from cutting interest rates but could significantly increase pressure on them to hike. As the market prices in Fed hikes at the same time tax cuts are considered by Congress, the US interest rate curve could bear steepen which would be very damaging for risk assets, especially emerging markets. Immigrant labour has been the primary driver of US population growth over the past decade making it one of the primary drivers of GDP growth.

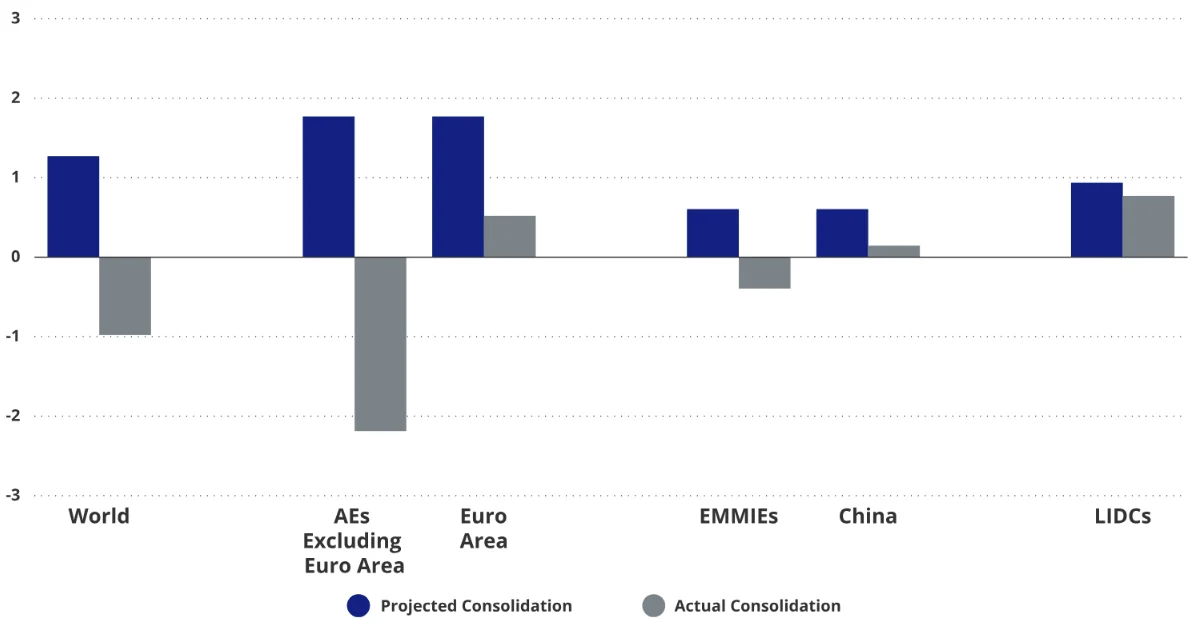

Failure to rebuild fiscal buffers and the same old concerns on the US debt trajectory

The IMF would like governments to use the current post-COVID period to rebuild fiscal buffers. However, developed markets have instead overpromised and underdelivered. In fact, outside the Euro area, developed markets promised to save and instead actually ended up spending more! In contrast, emerging markets implemented meaningful fiscal adjustments. Often the fiscal adjustment was because the EM economy was constrained by an IMF program or an inability to borrow more, but regardless of the reason the fiscal deficit was reduced.

Fiscal policy stance

Chart 2: Percentage points: 2024 minus 2022 primary balance

Source: International Monetary Fund; as of October 2024.

During the fall IMF meetings, concern over the sustainability of US fiscal policy and the trajectory of US debt was less pronounced than in recent meetings probably because over the past year the feared risks to markets from profligate US spending had failed to materialise. In other words, while it would be unsustainable to run the current level of US fiscal deficits indefinitely, it is not today’s problem and there is still (plenty of) time for the US to correct course.

In the US, interest expenses will soon make up half of the entire fiscal deficit. Because of this, the incoming Trump government may at some point decide that interest rates are too high and that the Federal Reserve should play a role in easing the burden on government. If at this moment the fiscal deficit were not significantly reduced (an outcome no one expects), this would be the moment when fiscal dominance would directly impact the market with the US dollar declining materially in value and long-term interest rates rising even as short-term interest rates declined. Without some form of yield curve control, the US government would need to shorten even further the average duration of its borrowing to benefit from the low short term funding costs. The first warning sign to watch out for will be an inability of US treasury to fund itself with additional long-term debt without causing a meaningful, negative impact on pricing.

Europe is still everybody’s favourite weak link

Europe remained everybody’s favourite weak link for the second year in a row. The region was a major beneficiary of the US-created order and rules, but these are increasingly challenged by BRICS and the US itself (especially under the Trump 2.0 presidency). As a result, Europe’s growth model of reliance on cheap Russian energy, rising exports to China, relatively low military spending, and low interest rates might no longer be viable. At least three of these factors are no longer there, and at the same time, the populist sentiment is staging a comeback across the region, driven by economic and energy uncertainty and insecurity, as well as immigration policies.

Over-regulation is another major issue, hitting Europe’s industrial core – Germany – particularly hard. The direction of Europe’s industrial policy is another major concern. According to a recent report from the IMF, industrial policy is driven mostly by climate mitigation, supply chain resilience, and security rather than competitiveness – the latter was the objective for only one-third of all industrial policy measures last year. Against this backdrop, structural reforms aiming to restore Europe’s competitiveness is an afterthought at best – perhaps with the exception of the former “periphery” (Greece, Portugal, Spain), which had an epiphany after its debt crisis a decade ago. It should not come as a surprise that the Eurozone’s real GDP growth is expected to stay close to 1% in real terms both in 2024 and next year. Downside growth risks in Europe will multiply if President Trump imposes a high uniform tariff on China, and this outcome will also be inflationary, posing additional policy challenges for the ECB.

No love for China despite the recent market rally

Investors remained unconvinced about China’s economic and market prospects, despite a string of policy announcements that encompass all key areas (monetary, fiscal, market, and regulations) aimed at boosting growth and revitalising the economy. Investors’ skepticism reflects, first and foremost, the fact that the recent previous attempts by China to reflate its economy lacked follow through with policy makers hitting the break soon after stepping on the gas. Investors second source of concern is the high odds of a tariff escalation under President Trump’s administration, which might also incentivise further strategic decoupling between the two countries that could ultimately lead to China being “uninvestable”. The key barometer to watch for how increased US-China tension over tariffs translates into EM assets will be how China decides to manage CNY deprecation. If it allows CNY to depreciate materially to absorb the loss of competitiveness from large US tariffs, it will lead to a material adjustment higher in the US dollar. However, if China decides it wants to prioritise stability in CNY in the face of tariffs in order to deter domestic capital flight and project maturity and strength to the world, EM assets will react positively.

Another major issue is that China’s stimulus so far has focused on reducing risks to local government balance sheets (it is not even large enough to resolve them) and not on stimulating domestic demand or reflating the property market. Policymakers are not implementing a shift away from China’s focus on industrial policy and instead are providing just enough support to achieve the government’s 5% growth target. By cutting tail risks in local government debt, including the reduction of “hidden” debt, it can free resources to boost consumption, social services, and investments in other projects at the local government level. In order to restore confidence in a sustainable way, however, the government may need to implement the measures it has so far avoided, including the development of the social safety net and taking measures to boost consumption in order to rebalance the Chinese economy. It makes a lot of sense for China to hold onto these additional measures as dry powder to use after President-elect Trump’s inauguration. A more bullish, market-oriented plan might only emerge in Q1-25 (at the earliest).

For now, China is rebalancing from real estate into new industries, and quite successfully, often producing better products at lower prices. This means, however, that China is likely to remain a major deflationary force in the world, whereas countries that put up protectionist barriers will end up with higher inflation pressures. This scenario bodes well for many EMs, those that embrace Chinese goods, and it will make their bond markets more attractive.

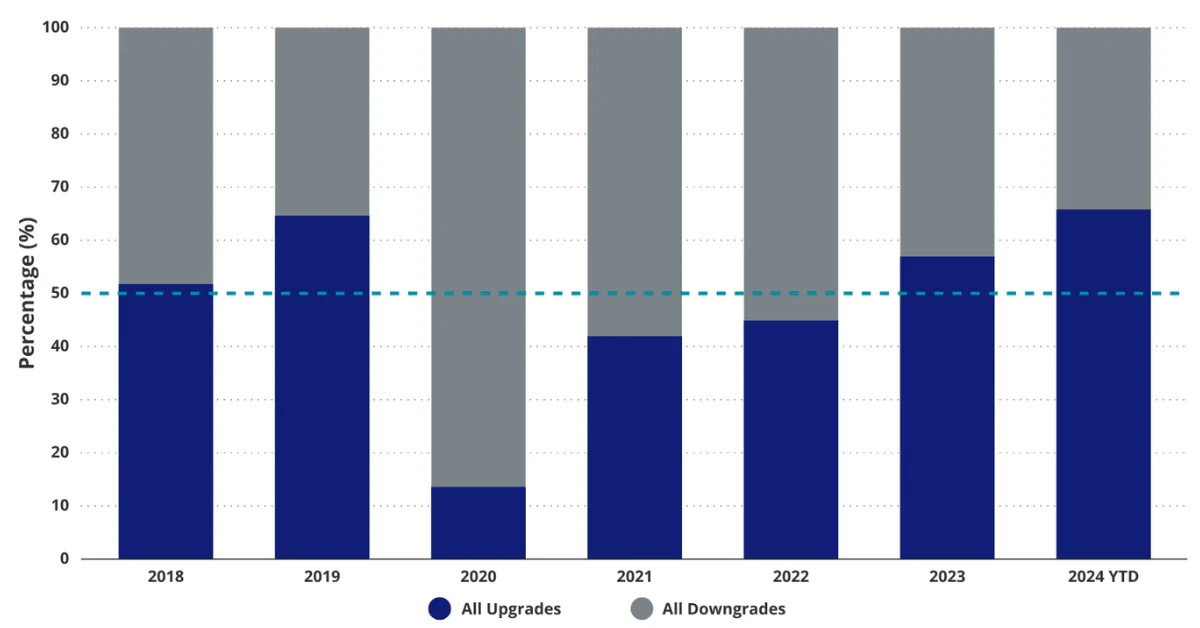

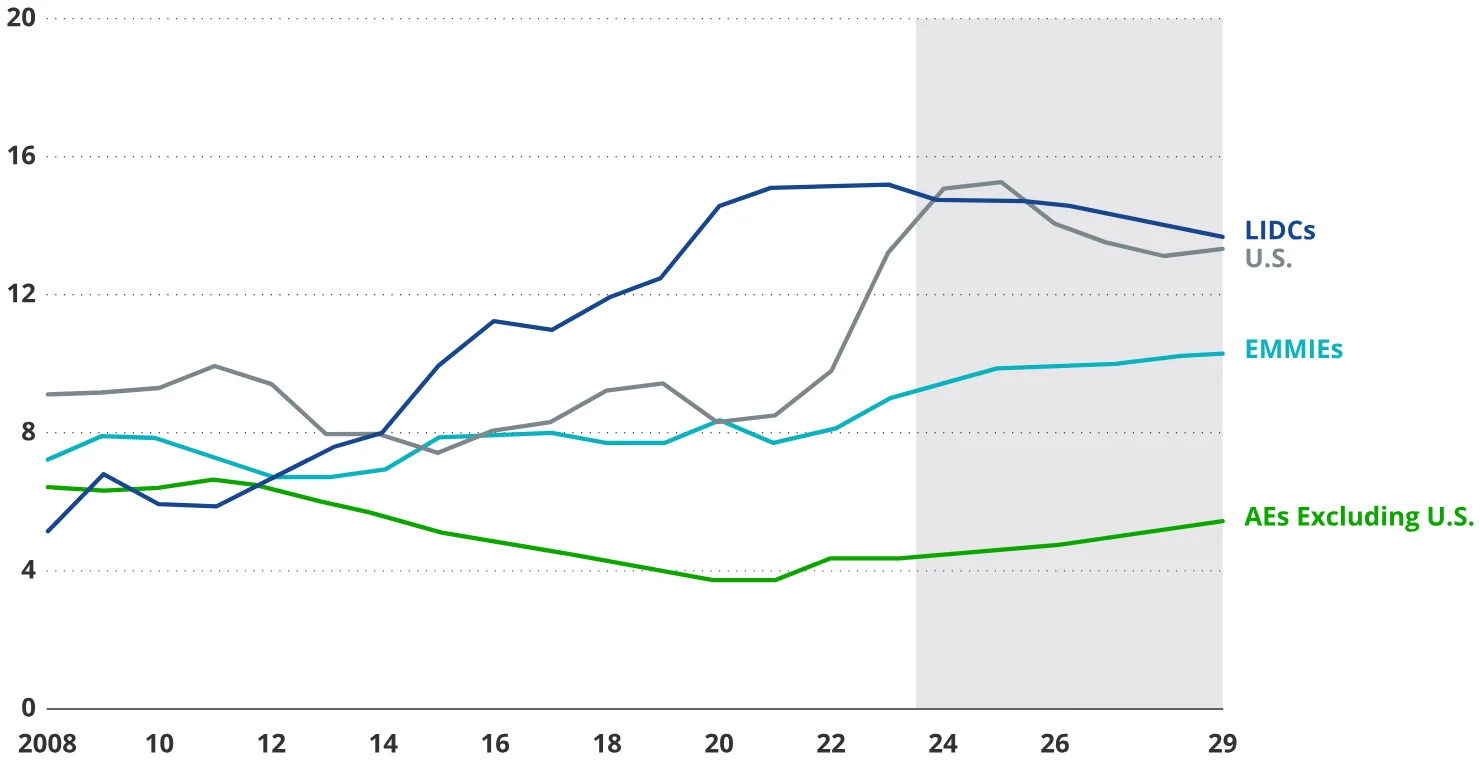

EM fundamentals vs. Global “pull” – Which one will prevail?

The rising influence of global factors in EM price movements is approaching a 15-year high in EM local debt and this makes US and Chinese policy uniquely influential at this moment. The benign interpretation of this fact is that with the US election uncertainty now over and global investors over hedged with respect to adverse policy stemming from the US focus can return to China policy stimulus and domestic economy fundamentals leading to positive price action. The recent wave of EM sovereign rating upgrades, which account for a big portion of this year’s rating actions, signals that EMs are entering this phase in better fundamental shape. However, lower income nations have been hit by a double whammy of social pressures associated with economic transformation and severe climate events, often without sufficient fiscal space to respond with corrective policy measures. It is reassuring that the percentage of economies experiencing social unrest is mostly lower than a few years ago, but the IMF programs in several low-income countries had to be adjusted to accommodate these risks.

EM sovereign ratings have improved over the past 2 years

Chart 3: Sovereign rating upgrades/downgrades (Moody's, Fitch, S&P)

Source: VanEck Research: Bloomberg LP.Top of Form

Many EMs are now facing a new domestic challenge of the fiscal policy trilemma. The IMF defines it as a combination of: (1) pressures to spend more on defence, climate, competitiveness, education, and health; (2) political resistance to taxation; and (3) the need to maintain public debt sustainability, and monetary and financial sustainability. The scope of the problem in major EMs and EM “Graduates” might be smaller than in the US, which now finds itself in the same group as lower-income countries as regards the share of interest payments in general governments revenue. Emerging markets have significantly lower debt/GDP ratios and generally smaller fiscal deficits than DM. However, there is no such thing in EM as fiscal “immunity”, especially in financial markets. Central Europe is facing the prospect of permanently higher defence spending. Asian EMs should tweak their growth models to accommodate structural shifts in China and commodity markets without jeopardising their hard-won macroeconomic and institutional credibility. And LATAM’s geopolitical advantages, “relative peace”, can no longer obscure concerns about fiscal consolidation.

General government interest payments

Chart 4: Percent of general government revenues

Source: IMF staff calculations.

EM’s attitude towards the fiscal trilemma will separate winners from losers in the coming years. However, EM fundamental and institutional evolution will not be completely independent of the post-election policy trajectory in the US, China’s attempts to reboot its economy, geopolitical shifts, and the reshaping of the international trade system.

The winners and losers under a Trump administration and major Chinese stimulus measures

EM winners: Argentina, Ecuador, El Salvador, Turkey, Israel, Saudi Arabia, Hungary, Zambia

Argentina, Ecuador and El Salvador were the clearest winners from a new Trump presidency due to easier access to additional IMF funding (as the IMF’s largest shareholder the US has an important say in lending decisions.)

Argentina needs to negotiate a new IMF program and desperately wants to get new money added to its already record size loan. Up until now, the IMF has been unwilling to increase the size of the loan to Argentina, especially given the unsustainability of the current exchange rate regime and concerns that the new money could be wasted defending the exchange rate just like under the Macri administration.

Ecuador is in compliance with its IMF program, runs a fiscal surplus and has rebuilt reserves. However, the country has faced electricity blackouts that last for up to 8 hours a day and there are concerns that this has damaged Noboa’s popularity and his chance at re-election next year. Additional support from the IMF and the US in terms of new lending to plug Ecuador’s financing gap in 2025 and help with additional generation capacity would go a long way to improving domestic sentiment and market confidence.

El Salvador is at an impasse with the IMF due to the nation’s bitcoin law and the IMF has indicated that it would not proceed with a lending program unless the legislation gets watered down. Trump is a fan of bitcoin and could help convince the IMF to accept the current state of affairs with regards to bitcoin in El Salvador.

Turkey will benefit from an improved political relationship with the United States as well as potentially lower oil import prices due to increased US production and maybe less scrutiny of Russian oil imports. Erdogan remains committed to Mehmet Simsek’s economic program that has been removing the relative price distortions in the economy including removing subsidies and hiking interest rates as well as implementing a fiscal adjustment. While the disinflation has been slower than hoped for to date, the approach is the correct one and so long as the Erdogan remains committed, inflation should return to target.

Israel will likely be able to count on greater support from the US government under a Trump administration, strengthening its position in the Middle East, and a subsequent refocus on the Abraham Accords.

Saudi Arabia considers President Trump a top international ally, and the country would be a key beneficiary of easing regional tensions through trade channels, financial linkages, and FDIs in strategic sectors. Still, the prospect of wider budget deficits, smaller current account surpluses (or even deficits), and issuance concerns are clouding the sentiment. Investors might be willing to overlook these issues if geopolitical risks subside, but the deteriorating fiscal (and arguably external) metrics might not be fully reflected in valuations.

Hungary’s Prime Minister Orban established a strong rapport with President Trump during his first term in office, and there is no reason why this relationship will not continue in the next 4 years - especially as the two leaders seem to share views on the resolution of the Ukrainian conflict and Hungary’s role in it. It remains to be seen though whether this will speed up the disbursement of the EU funds. Geopolitical tailwinds aside, Hungary’s fiscal consolidation progress got a nod of approval during the IMF meetings, which is a boon against the backdrop of ample domestic liquidity.

Zambia should benefit from improved copper production and investment next year as well as potentially higher copper prices if the demand outlook improves due to China’s stimulus. It has started to rain again and if this continues it can help improve the outlook for power generation and prospects for a recovery in the harvest. Additionally, with the recent success of their sovereign bond restructuring, the yields on Zambia’s local bonds have fallen rapidly and the government can benefit from lower funding costs.

EM losers: Mexico, Poland, Romania, Colombia

Mexico will need to endure a similar negotiation process as under Trump’s first administration where it will need to promise to limit migration across the shared US-Mexico border in exchange for avoiding new tariffs from the US. While it should be an easy agreement to reach as there is a precedent and process already, it will be the first geopolitical test for the new Sheinbaum administration.

Poland would likely need to divert more resources to military spending should the Trump administration decide to reduce US involvement in NATO adding additional spending onto already high fiscal deficits.

In Romania, one difficult-to-weight and difficult-to-time risk in Romania involves neighbouring Moldova. Moldova has a pro-European government that was just re-elected. However, concerns about Russia’s influence and how to resolve ethnic tensions could come to the fore, depending on the trajectory of both the Ukraine conflict, but also depending on the regional and global power calculations following any “end”.

Colombia’s President Petro continues to push the boundaries of the country’s institutional frameworks with the proposal to increase distributions to regional governments threatening to veer the government debt stock towards unsustainability. Fortunately, Petro has been largely unsuccessful to date, proving the strength of Colombia’s institutions. In a positive twist, Petro recently announced larger than expected budget cuts into year end to ensure the government’s compliance with this year’s fiscal rule.

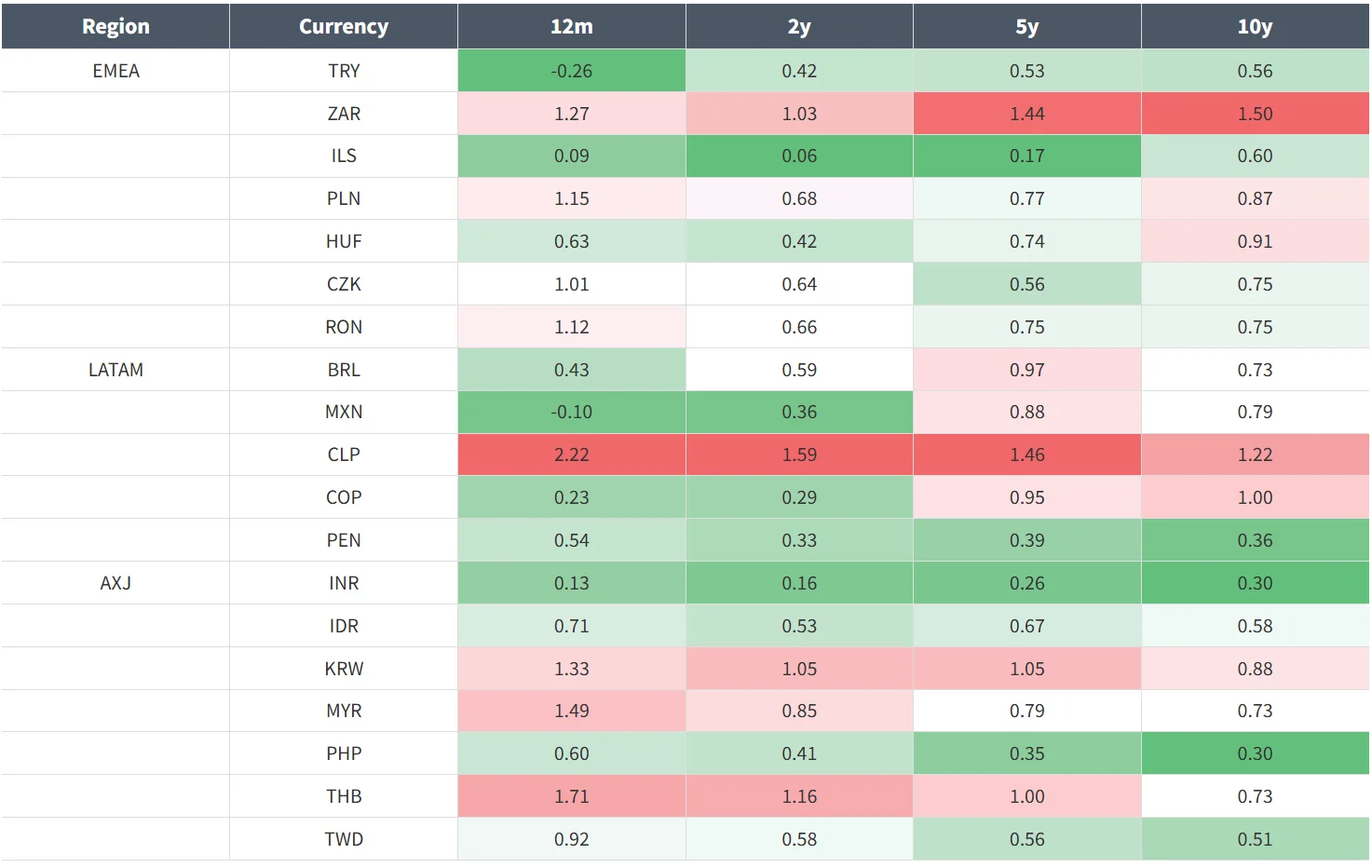

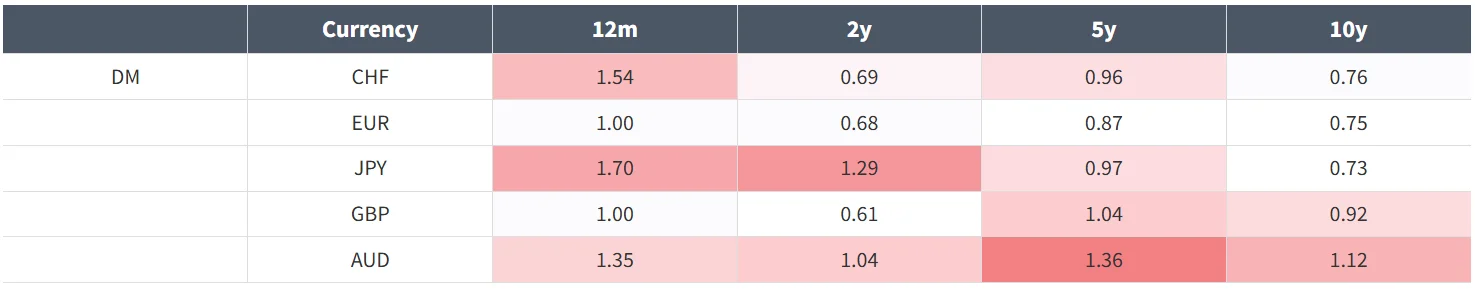

EM FX with a high Beta to CNY will be a loser in a scenario where aggressive US tariffs on Chinese goods lead to a large, one-off devaluation of CNY against the USD. CLP, THB, MYR, KRW and ZAR would be the most impacted. The table below is a useful guide to judge the relative sensitivity of global FX to a CNY devaluation.

Table 1: 11/12/2024 - EMFX Beta to CNY (based on % weekly change)

Table 2: 11/8/2024 - DMFX Majors Beta to CNY (based on weekly % change)

Source: VanEck Research.

Published: 20 November 2024

Any views expressed are opinions of the author at the time of writing and is not a recommendation to act.

VanEck Investments Limited (ACN 146 596 116 AFSL 416755) (VanEck) is the issuer and responsible entity of all VanEck exchange traded funds (Funds) trading on the ASX. This information is general in nature and not personal advice, it does not take into account any person’s financial objectives, situation or needs. The product disclosure statement (PDS) and the target market determination (TMD) for all Funds are available at vaneck.com.au. You should consider whether or not an investment in any Fund is appropriate for you. Investments in a Fund involve risks associated with financial markets. These risks vary depending on a Fund’s investment objective. Refer to the applicable PDS and TMD for more details on risks. Investment returns and capital are not guaranteed.