Smart beta vs. active management: The investment evolution

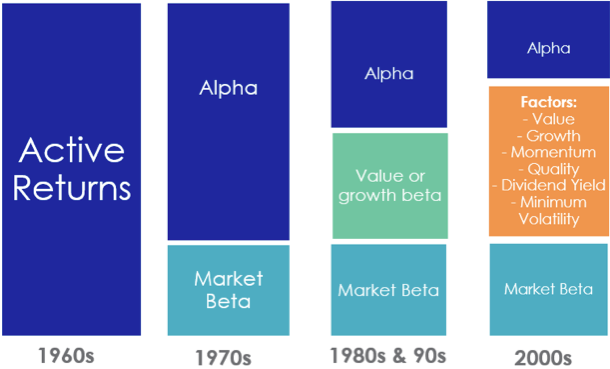

You may have seen this diagram, or an adaptation of it, before:

Source: VanEck

Or maybe you haven’t. It’s an attempt to illustrate how attributing a professional active investment manager’s skill has changed over time.

In the 1960’s an active manager’s return was only compared to another manager’s return. Whoever returned the highest was considered to be the most skilful.

Toward the end of the 60’s as research by Harry Markowitz and William Sharpe emerged, market capitalisation indices become the standard measure of the stock market. It was against this barometer active managers’ returns, and the standard deviation of those returns, were compared. The Greek alphabet became the lexicon for this.

‘Alpha’ is the term commonly used to describe performance above a given benchmark market capitalisation weighted index. ‘Beta’ refers to the performance of the market represented by that index. In Australia the standard market benchmark, and therefore the standard measure of beta, is the S&P/ASX 200 Index.

In the 80’s and 90’s, following more research and analysis of portfolios, stock pickers were described as: value managers; growth managers; or GARP (Growth at a Reasonable Price) managers - which is a combination of value and growth. Value managers were those that focused on identifying stocks which were trading at what they believed was a discount to their fair value. One way to identify value stocks is to pick those with a low price-to-book value. Growth stocks, on the other hand, were identified as companies whose earnings were expected to increase at an above average rate. These are often smaller companies. In the 80’s and 90s a fund manager’s returns could be attributable to a combination of:

- beta;

- the style of the portfolio eg value or growth; and

- alpha.

For the first time alpha was recognised as the performance attributable to the manager’s skill, not just beyond the market, but beyond the returns attributable to the style of the portfolio. The portion that is attributable to alpha, as illustrated by the diagram above, is getting smaller.

More sophisticated research into the persistent drivers of stock returns saw the rise of identifiable ‘factors’ beyond value and growth as well as factor indifferent approaches such as equally weighting a portfolio. These more recent factors identified as persistent long term drivers of returns include: minimum volatility, high dividend, quality and momentum. Technological advances and the dramatic increase in the availability of data or “big data”, as it is commonly called, have seen more of an active stock-picker’s returns attributed to market beta and factors.

The result is a reduction in the part of the return which can be attributed to the managers skill. Active managers need to be able to demonstrate that their individual skill is generating sufficient alpha to justify their fees. Consequently active managers are now, more than ever before, under pressure to justify their fees.

At the same time as all this has been happening, index or ‘passive’ investing has been on the rise. Initially, the aim of the passive manager was to track the benchmark index and achieve the returns of the market, or beta, minus their fees. Those fees are less than active managers’ fees because passive investing doesn’t require the same level of analysis and therefore less staff. Many people found this a good trade off because while actively managed funds sometimes outperformed, sometimes they did not while passive funds achieved just below market performance for lower fees. These passive funds were thought of as average, not high, not low, just the market performance and throughout the 70s, 80s and 90s they started to become popular.

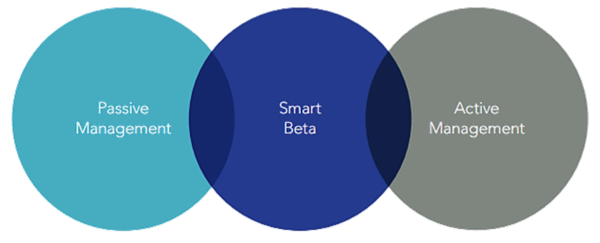

ETFs (exchange traded funds) have since revolutionised passive investing. New index design innovations that include factors are now being tracked by passive ETFs which have been delivering targeted outcomes which exceed those of most active managers over the long term, while retaining the low costs of index investing. This is smart beta, the intersection between passive and active investing.

Source: VanEck

There are now many low cost smart beta ETFs which deliver the ‘factor’ returns beyond market beta. They do this by tracking smart beta indices which are specifically designed with targeted investment outcomes in mind. Smart beta has been identified as:

“a disruptive financial innovation with the potential to significantly affect the business of traditional active management. They provide an important component of active management via simple, transparent, rules-based portfolios delivered at lower fees.” (Kahn and Lemmon, 2016)

Advisers and their clients are now assessing if their active managers are providing sufficient alpha beyond the returns provided by market beta and factors, leading many savvy investors to change to smart beta, attracted by their targeted outcomes, lower fees relative to active management, transparency and ease of use via simple trades on ASX.

Published: 05 July 2019